In this chapter, a comparative textual analysis was done on the following four films: See No Evil, Hear No Evil (1989), Mr. Holland’s Opus (1995), Copying Beethoven (2006), and Dig (2022). I identified similarities and repeated patterns in these films and addressed them. I went beyond what was seen, and I argued what could be done differently.

1. Deaf vs Stupid

InSee No Evil, Hear No Evil, Dave and Wally are wrongly arrested for murder. The inspector doubts they are the murderers and wants to investigate further. But the chief of police is furious and has no empathy or understanding towards both the deaf and blind men. He says to the inspector, ‘You’re always feeling sorry for people, that’s your trouble. I’ll take care of this.’ The chief of police goes into the interrogation room where Dave and Wally are sitting. Standing behind Dave, he starts talking. Of course, Dave can’t hear a word. ‘He’s deaf, you have to be facing him,’ Wally explains. Irritably, the chief of police walks around the table so Dave can see him, but now he talks too fast. Dave still doesn’t understand. Wally tells the chief of police to repeat the question. Even more irritated, he repeats his question, but now exaggerates the words and talks considerably slower. ‘Was… there… a… woman… present… (at the crime scene)?’ Dave replies with the same effect. ‘Yes… there… was… a… woman… present…’ The chief of police turns to Wally and asks, ‘Why is he talking like that?’ Wally gives a pointed answer, ‘Because he’s deaf, not stupid.’

The fact that the chief of police isn’t equipped to handle persons with disabilities in a professional capacity, and the fact that he believes he’s superior, shows that audism is clearly shown here. Prejudice and discrimination are portrayed through the chief police’s attitude. It shows that he assumes Dave is stupid simply because he can’t hear. This is a harmful stereotype. His actions are condescending because he speaks slowly and exaggerates his words to great effect. The chief of police is also ignorant when it comes to Dave’s communication needs, for he doesn’t recognize that Dave needs assistance in the form of an interpreter. Wally’s answer – “Because he’s deaf, not stupid” – challenges the chief police in how he views d/Deaf persons. Finally, because the chief of police’s attitude has a sense of superiority, he portrays the power dynamics that often belittle and exclude persons with disabilities. Wally’s response – “deaf, not stupid” – reminds us that honor and respect towards individuals with disabilities is critical, as it forces us to go beyond physical limitations, and see the person in their humanity and intelligence.

In Copying Beethoven, Beethoven’s relationship with the hearing world is fraught and strained. When Anna visits Beethoven for the first time, she knocks on his door. The next-door neighbor neighbor opens up instead and tells Anna to just go into his apartment. ‘He can’t hear anything. He’s deaf, you know.’ Awkward misunderstandings also ensue between Beethoven and his nephew, Karl. ‘I’m a bit short,’ Karl says when Beethoven invites him for lunch – meaning he doesn’t have the cash to dine out. But Beethoven thinks he means that he’s literally short. ‘Nonsense, you’re taller than me,’ Beethoven replies. The nephew decides to leave it alone and doesn’t clear up the misunderstanding. This response is a clear example of what it’s like to isolate and exclude the d/Deaf person from society. Social interactions like this – or the lack thereof – can cause alienation and anxiety in the d/Deaf person, causing them to withdraw even more. This in turn fuels depression in d/Deaf persons, which is already a daily battle that they have to face. “Medical studies have found that deaf people suffer from mental health issues at about twice the rate of the general population…” (Marcia Purse, 2021)

The scenes from this film are a clear portrayal of the social struggles of a deaf person in a hearing world. These scenes painfully show the isolation and exclusion Beethoven experiences, which further alienates him from society. The conversation between Beethoven and Karl – his nephew – shows how easily misunderstandings can develop. When Karl doesn’t clear the misunderstanding between them, it deepens Beethoven’s social isolation, depression, and anger. As for the neighbor, her comment that “he can’t hear anything” also reinforces the tendency to put deaf individuals in a box, stripping them of any humanity and complexity. This also causes a division between the deaf individual and the hearing community. Living in a predominantly hearing world can be exhausting for persons with hearing loss, which adds to the frustration and misunderstandings. Lack of empathy also develops in such settings, and it shows the painful reality in which deaf individuals have to function. Greater awareness needs to take place so that the deaf person can be included in society.

In Mr. Holland’s Opus, The Beatle’s John Lennon passes away; and the father is heartbroken. Cole, the son, asks his father what’s wrong. His father says, ‘You wouldn’t understand.’ The son goes after him and tells his mother to interpret for him. ‘Why do you assume I wouldn’t understand? I know who John Lennon is. I’m not stupid.’ My interpretation is that the father is not equipped with how to speak to his son, and he has no grasp of the depth of his son’s knowledge of the music industry. The father doesn’t make any effort whatsoever to build a relationship, and this results in the father having misconceptions about who his son really is and whether he has the intelligence to grasp music.

This scene clearly shows the nature of audism. The father shows bias towards his son, not only where his hearing is concerned, but also his intelligence and capacity to grasp complex concepts such as music. The father simply assumes that his son has no apprehension when it comes to John Lennon’s death. This is a clear example where society as a whole underestimates the intellectual capabilities of a deaf individual. The father subconsciously portrays audism towards his own son, simply because they have no relationship whatsoever. Cole’s response, “I’m not stupid,” is heartbreaking, but he uses his voice to empower himself. In return, the audience is educated dramatically.

2. Equality vs Inequality

In See No Evil, Hear No Evil, the strained relationship between Dave and the hearing characters is portrayed in a painstakingly realistic way. In the very first scene, the minibus driver shows disrespect to Dave and makes an obscene gesture. Dave, still confused about what happened, returns the favor. There is no equality where Dave is concerned – there should be signs and signals up on the streets helping persons with disabilities to understand what’s going on. In the bar scene, Dave meets up with Wally and his friends. Dave accidentally steps onto a man’s jacket, and the man turns around and is rude and threatens to hit him. Dave doesn’t hear him, so the man shoves Dave and he tumbles backward. ‘Sorry, I didn’t know I was standing on your jacket,’ David apologizes. The hearing characters view Dave as ‘dumb’ and ‘stupid’ because he doesn’t always understand what goes on. The hearing characters don’t see Dave as their equal. Later on, Dave and Wally’s ‘lawyers’ arrive at the police station, and they promise to have them out of jail by 5 o’clock. They comment, ‘We’re pushing the blind and deaf angle. Hope you don’t mind.’ ‘No, we don’t mind. Use it,’ the blind guy answers. This is discrimination because a person with disabilities should not be treated any differently than a person with no disabilities. But at the same time, there’s a fine line, because persons with disabilities do have certain special needs that have to be met, like an interpreter was needed during the interrogation at the police station.

Inequality is shown in this scene, especially through Dave, who has a disability. This film shows the disrespect, exclusion, and societal attitudes portrayed towards persons with disabilities. The minibus driver’s attitude towards Dave is a clear portrayal of ableism. The bar scene fight escalates quickly simply because of misunderstandings between Dave and the hearing characters. The police station scene shows the fine line between accommodation and exploitation. Dave and Wally’s disabilities are exploited so that they can get out of jail. This film is a comedy, and certain scenes are exaggerated for greater effect, but it also shows how stereotypes are reinforced when it comes to persons with disabilities.

In another scene, Wally asks Dave what he wants out of life before his life is over. ‘Not to make a fool out of myself,’ Dave answers. ‘I have this terrible fear, that I’m going to make this huge mistake, and everyone’s going to stand around and stare at me.’ This is linked directly to his hearing loss. As the film progresses, it is obvious that Dave and Wally try to hide their disability from the world. They don’t want to be viewed as ‘different’ or treated differently. Dave believes that the world sees his deafness as a disability, so in return, he also handles his deafness as a disability.

Dave’s fear that he will make a fool of himself shows the stigmas and stereotypes that surround persons with disabilities. In the 1980s, misconceptions were still deeply embedded in society when it came to deafness. Dave doesn’t want to be seen as different, and this causes anxiety within himself. He tries hard not to make any mistakes, and he especially doesn’t want to be judged unfairly. These scenes show the fear that comes with the myths and prejudges persons with disabilities experience in society.

In Mr. Holland’s Opus, Mr. Holland learns how to connect with his hearing students, but he struggles to connect with his deaf son. The deaf son is introduced in the film as a healthy baby. After his parents find out he is profoundly deaf, there is evident devastation from the parents’ side. The doctor advises the parents that they ‘treat him as if he’s normal’. But his father is not convinced and still believes his son cannot be his equal. The relationship becomes strained for many years. Mr. Holland’s son is clearly shown as being part of the Deaf community, as he goes to a school for the Deaf, learns sign language, and is surrounded by Deaf friends. My interpretation is that whenever his son wants to enter his father’s hearing world, his father simply rejects him without giving it a second thought. His father does not see his son as his equal – at all.

Mr. Holland and his deaf son have a strained relationship, which is emphasized by the anger and frustration that often develops between them. There is also deep-rooted bias. Mr. Holland is devastated when he finds out his son is deaf. The fact that he refuses to see his son as his equal, reflects a common trait found in parents who struggle to accept their child’s disability. Parents have high hopes when it comes to their children. In this case, Mr. Holland believes that his son will never measure up to his own expectations, especially where the world of music is concerned. The father also rejects his son’s Deaf identity, and this furthers the gap between them and widens the divide.

In Copying Beethoven, the opposite is found to be the case – to some degree. Beethoven believes he is everyone’s equal; in fact, he also believes that he is even higher than everyone else. At one point he says, ‘God whispers into some people’s ears. Well, He shouts into mine. That’s why I am deaf.’ He believes he has been specially chosen to compose the music of heaven. However, others don’t view him the same way. It is clearly shown in one of the final scenes, where Beethoven gives a private orchestra performance to the pope. It’s a disaster, but Beethoven is unable to hear it. When the performance finishes, the pope stands up and says, ‘My God, you’re deafer than I thought.’ Once again, the society in that age had no education or training where persons with disabilities were concerned. It is my interpretation that the pope had no compassion or understanding where Beethoven was concerned, thus Beethoven was no longer seen as the pope’s equal.

The tense dynamic between Beethoven and the hearing society shows the judgment that comes with disabilities. Beethoven is a confident maestro, and he refuses to see his deafness as a limitation to living out his unique and divine role on earth. He even believes that he has been put on a higher pedestal than his peers, family, and friends. But the pope’s comment after Beethoven’s disastrous performance shows that society doesn’t see him that way at all. The pope has a lack of understanding and compassion, and he inadvertently strips Beethoven of any dignity he has left.

3. Hearing vs /Deaf Actors

In See No Evil, Hear No Evil, a hearing actor, Gene Wilder, was cast for the role of Dave. Because the character of Dave is in no way showcased as part of the Deaf community in the film, I would argue that it is accurate that a hearing actor was cast in the role of a deaf person. It is interesting to note that the Deaf community is excluded in this film. Why did the filmmakers decide on this? Was it a conscious or a subconscious decision? Wally is shown as being isolated from society, but if he had been part of the Deaf community, he would not have felt isolation to such a high degree. The decision to cast a hearing actor to play the role of a d/Deaf character shows that the filmmakers had the hearing community in mind as their target audience. The filmmakers may have decided to create Dave’s character in such a way that it fit the comedic elements of the narrative, instead of accommodating the d/Deaf community. This is another example of how mainstream media often overlooks the reality of d/Deaf life and its challenges. This film chose to revert to stereotypical characters instead.

In Copying Beethoven, another hearing actor, Ed Harris, was cast for the role of Beethoven as well. Since Beethoven lost his hearing later in life and was still able to compose music, his deafness did not define his life or identity. Beethoven’s struggle with high-frequency sounds highlights the complexities of his hearing loss. Because the character of Beethoven struggled only to hear high-frequency notes, it is fine that a hearing actor was cast in this role. However, this still raises the question of the representation of disability in film and whether d/Deaf actors were overlooked so that a well-known hearing actor could be cast instead.

In Dig, Thomas Jane’s daughter, Harlow Jane, was cast in the role of Jane, who is deaf and mute for most of the film. This film raises important questions when it comes to authenticity and correct representation of the d/Deaf. Because Jane was a hearing person at the start of the film, she lost her hearing due to a traumatic event. She also lost her speaking voice after the traumatic event, so she resorted to sign language and lipreading as a means of communication. Because Jane grew up in the hearing society, she probably still views herself as hearing and hopes to get her hearing back soon. In this case, it was appropriate to cast a hearing actor in this role.

Out of all four films, only one d/Deaf role was given to a real-life Deaf actor: Anthony Natale in Mr. Holland’s Opus. Further research shows that Anthony Natale is part of the Deaf community and views himself as proudly Deaf. In this case, it was proper to give this role to a Deaf person. Job opportunities were created for him, and this film kick-started his career as a successful actor. (Anthony Natale, 2022) Natale also did an authentic portrayal of the Deaf community, and it is a significant and positive example of accurate characters. This casting choice is a powerful step towards inclusive and diverse representation where d/Deaf actors and characters are concerned.

4. Misrepresentation of Lipreading

In Dig, it is identified that lipreading is portrayed as Jane’s superpower. She can lipread the kidnappers’ mouths when they are standing in the kitchen. Her eyes zoom in on their mouths, and the camera shows us what she ‘hears’ through ‘seeing’. When Jane’s father speaks to her, the sound cuts out as well and the camera zooms in on his lips as she ‘reads’ them. This is an inaccurate representation of lipreading, for the room was too dark for Jane to have been able to understand the conversation. Later on, Jane attempts to escape. The bad guy fires a shot and she falls to her knees. It’s unclear why she fell to the ground since she shouldn’t be able to hear the shot… The kidnapper then rushes over to her and says, ‘Read my lips…’ He then threatens to kill her if she doesn’t listen to him.

Several factors need to be taken into consideration when it comes to lipreading, according to RNID: You need to have great focus and good eyesight; the environment and area should be well-lit and have no darkness at all; some words tend to be formed the same way at the mouth – which makes misunderstandings inevitable; mustaches, accents, and beards also make it extremely difficult to lipread clearly, etc. (RNID, n.d.) These scenes portray lipreading as a superpower, but it’s a survival skill that Jane had to learn after she lost her hearing overnight. This film oversimplifies lipreading as a superpower, or a magic trick. That is not the case at all.

In See No Evil, Hear No Evil, in the bar fight scene between Dave, Wally, and the man, a fourth man joins the fight. He says to Wally, ‘Read my lips’ and then attempts to hit him. Dave also lipreads his ‘lawyer’s’ lips, who is the killer. He can lipread valuable information from afar which will later save them. Lipreading is something d/Deaf persons are forced to fall upon when they don’t have a clear understanding of what is said to them. In this case, lipreading is used as a plot point in these scenes to move the story forward and is not shown as a survival skill, which it really is. These scenes downplay just how complex and challenging lipreading is.

In Copying Beethoven, Anna talks to Beethoven’s previous copyist. The componist discusses Beethoven’s hearing abilities: ‘It’s the rehearsals… and he insists on conducting. What’s he going to do? Lipread?’ He tells her that the last time Beethoven composed an orchestra, he threw them off badly. Because Beethoven still has some of his hearing, it is unclear to the audience whether he does have lipreading skills, and the film does not elaborate on it. Lipreading is a unique skill that some – not all – d/Deaf persons have. Lipreading is… “the ability to recognize lip shapes, patterns, and facial expressions to understand what is being said.” (RNID, n.d.) Lipreading is also mostly guesswork, and it is not always 100% accurate. In the case of Beethoven, lipreading is used as a communication skill, at which he seems to fail miserably.

5. Connection and community

In Mr. Holland’s Opus, the father has a strained relationship with his son until the very end because of his hearing loss. Mr. Holland understands almost no sign language, and he doesn’t make an effort to learn. ‘Why is every other child (in your class) more important to you than your child?’ the mother asks the father in one scene. The relationship between father and son is broken and fraught. A heated conversation about John Lennon between Cole and his father makes his father realize how much he doesn’t know his son, and he sets out to change that. He arranges an orchestra concert with different colors of lights flashing in the background. This invites deaf persons to partake in the music. An interpreter stands on the stage when Mr. Holland explains that they are going to do a song, Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy) by John Lennon. He also dedicates the song to his son, Cole. He sings the song in sign language and with his audible voice. It is my interpretation that the father and the son finally connect in this emotional moment. From there on, Cole is invited into his father’s world and his community widens as he listens to music by sitting on the speaker at home and feeling the beat and rhythm of the songs. For any person – whether they have a disability or not – it is important to have connection and community around them. Family even more so. These scenes show how we can change the audience’s perception of inclusivity where d/Deaf persons are concerned. The emotional arc between Mr. Holland and his son, Cole, highlights just how powerful connection, understanding, and inclusiveness are. The fact that the father also went out of his way to make the Deaf community part of the orchestra performance, is a practical and important step in the right direction – inclusivity for all groups. The turning point that comes when Mr. Holland realizes he can bridge the gap between the hearing world and his son’s world, is a beautiful and emotional moment to behold.

In an earlier scene, the father tells the story of Beethoven in his classroom, and how Beethoven did everything he could to connect to music. The disappointment and sadness are evident on the father’s face, as he feels that his child will never hear nor appreciate music the same way that he does. This scene shows how hearing persons often think that d/Deaf persons cannot appreciate nor understand music when that is simply not true. But in fact, d/Deaf persons can enjoy music, even if it’s a limited understanding of frequencies. Vibrations from music also enable deaf persons to enjoy music on another level that perhaps a hearing person would not be able to grasp or understand. In fact, “music is very multi-sensory, which is why deaf people can feel the vibrations produced by the music being played and consume those vibrations through their body.” (ConnectHear, 2020)

In Copying Beethoven, at the premiere of his new music, Anna helps Beethoven by sitting obscurely among the orchestra members on stage. She shows him what he needs to do with his hands as maestro, as he can’t hear the high frequencies anymore. At the end of the composition, she discreetly stands up and shows him to turn around so that he can see the audience cheering and clapping for him. He can see their responses and connect to the audience. This scene shows a creative way of making persons with hearing loss part of society. The fact that Anna went out of her way to sit among the musicians, and chose to hide so as not to embarrass Beethoven, shows an empathy and grasp for Beethoven’s situation. When Beethoven turns around to view the audience clapping their hands, there is some confusion there again, for why wouldn’t he be able to hear (or feel) the loud sounds of thousands of people clapping their hands? Again, the frequency of hearing loss that Beethoven has here is a bit unclear. But the fact that Anna shows him that he needs to turn around and experience his praise fully, shows how he is being included in society. Once again, it shows that while challenges still exist, with empathy and adaptation, individuals with disabilities can still engage meaningfully in society.

In the final scene of See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Wally asks Dave, ‘How does it feel to be handicapped? I’ve always wanted to ask you.’ Dave warmly replies, ‘I’m not handicapped. I have you.’ It reveals the profound connection and mutual understanding that exists between the two characters. It also shows how Wally, a hearing person, has made Dave feel part of society simply by being his friend. This moment on the screen highlights just how the foundations of community are built upon empathy, support, and acceptance. Inclusion isn’t about the absence of disabilities, but rather about being seen and heard. Community provides a space where everyone is valued for who they are. Community is all about connection, being heard, and being understood.

6. Deaf accents

In See No Evil, Hear No Evil, when Dave speaks onscreen for the first time, he doesn’t have a deaf accent. Throughout the whole film, he speaks like a hearing person and doesn’t use sign language as a means of communication. He tells Wally, his blind friend, that he wasn’t born deaf; he got scarlet fever in high school. Gradually, his hearing disappeared until it was completely gone. The film does not address how his speech patterns and accent would’ve evolved over the years, as he still speaks exactly like he did before he lost his hearing. I would argue that this is not an accurate representation, as he has been unable to hear himself for many years now. Dave’s character is a misrepresentation of what a person’s voice should sound like after years of not being able to hear your own voice. It is also not shown whether Dave went for speech therapy lessons after losing his hearing, which is what should’ve happened for him to keep his ‘hearing voice’ – although it inevitably would’ve changed to a slightly deaf accent as the years went by.

In Copying Beethoven, Beethoven speaks like a hearing person, with no traces of a d/Deaf accent. He gradually started losing his hearing over the years. We come to notice that he is not profoundly deaf, but only hard of hearing. ‘Deafness’ is too extreme; in this case, the actor doesn’t need to have a ‘deaf accent’ as he still has some degree of hearing left. This accurate portrayal enhances the authenticity of the diversity and wide spectrum of hearing losses.

In Dig, When Jane finally regains her hearing and speaks again in the end, her voice is not hoarse at all from not speaking for a year. She also doesn’t have a deaf accent. I would argue that this is also not realistic, because a person’s voice box is a muscle that needs to be exercised and used regularly to be able to speak. (Web Desk, 2024) Prolonged disuse of the vocal cords can lead to vocal atrophy, which should’ve been shown in this film when Jane speaks again. How is it possible that Jane can still speak so clearly after such a long time of not speaking with her voice – with no d/Deaf accent at all? This film doesn’t show whether she had any speech therapy or vocal practices during her year of silence. Regaining full hearing doesn’t automatically result in an ability to fully speak clearly again.

7. Communication

In See No Evil, Hear No Evil, the first scene opens with the bustling noise of traffic, construction, and ambulances in New York City. Dave walks down the street, oblivious to the noise around him. He stops in the middle of the street, and a minibus hoots at him; he remains standing. ‘What are you, deaf? Look behind you!’ shouts a taxi driver going by. Dave doesn’t respond… he doesn’t even blink. People behind him are shouting at him and the taxi driver, and yet he remains oblivious. Finally, he turns and sees the minibus driver mouthing ‘You dumb idiot!’ The camera zooms in on the lips, and through lipreading, Dave realizes with shock that he is in the way. He jumps back onto the pavement in a hurry. I would argue that this scene is not an accurate representation of a truly d/Deaf person. Wally has been living in New York City for many years, and his other senses would be extremely heightened due to living in a bustling city like NYC. He would been keenly aware of his surroundings, and it is doubtful that he would be caught unaware in a situation like this. It can be argued that this film is a comedy, and that’s why humor is valued above accuracy. But it still reinforces inaccurate stereotypes and portrayals of d/Deaf persons and their keen sense of awareness.

In various other scenes, Wally (the blind man) is frustrated that he has to repeat everything he says to the deaf man. In one scene, he screams into Dave’s ear to see if he can hear anything (which he can’t). Although this is a disrespectful act to do towards a deaf person, it is a realistic portrayal of how a hearing person is inevitably bound to get irritated towards a d/Deaf person. Once again, comedic elements are of high priority in this film, and that’s why the dynamics are exaggerated.

In copying Beethoven, our introduction to Beethoven is likewise the same. He is aggressive and explosive in his manners and words. ‘I’m a very difficult person, but I take comfort in the fact that God made me that way,’ he explains to Anna. Someone tells Anna, ‘It’s as if his (Beethoven’s) soul’s gone deaf. He was a romantic… then something changed.’Because Beethoven used to have normal hearing for most of his life, it is accurate to show that he would become aggressive and frustrated with losing his hearing skills. He’s been a musician and composer for most of his life, and if his hearing is taken away, what’s left for him to do? For a hearing person, it can be daunting and scary to lose their hearing. But for someone who grew up deaf, it’s much easier to adapt, change and be flexible.

In Mr. Holland’s Opus, there’s visible frustration between the deaf child and parents because the child struggles to communicate his needs. The mother is desperate to communicate with her son. ‘I want to talk to my son,’ she tells her husband. They decide to put their child in a deaf school so he can learn sign language. At the deaf school, the headmaster tells the parents, ‘The most important teacher your child will ever have is you.’ She encourages the parents to sign up for sign language classes. These scenes identify the Deaf community and culture, and how sign language is important to them. The fact that the parents – even if it’s just the mother at first (the father joins them later on) – decide to adapt to their son’s brand new world of sign language, shows that communication is important to them as a family.

8. Sign Language & other methods

In Mr. Holland’s Opus, Cole’s parents are uncertain what to do about his deafness. As a result, he spends most of his childhood in complete silence and without any proper communication skills. When it’s time for him to go to school, his parents enroll him at a school for the deaf. There he learns sign language for the first time, and this empowers him with the necessary tools to express himself and connect with others. The teacher encourages the students to sign and use spoken language at the same time. Cole learns to communicate, and as a young adult, he signs and speaks with his voice at the same time. This film is an accurate representation of the Deaf culture and community, and it clearly shows that Cole grew up in a Deaf culture. Cole’s journey – from silence to fluency in sign language and spoken language – is a brilliant representation of the transformative impact of access to the necessary and appropriate education, as well as communication methods.

In Copying Beethoven, When Anna enters the apartment for the first time, she sees Beethoven playing his piano, wearing a homemade tin foil over his head. He doesn’t hear her and gets a fright when she hovers over him with her shadow. He appears to only be hard of hearing – not deaf – as he only misses out on a few words. Anna has to repeat herself a few times and speak louder. He explains what the tin foil is over his head. It is a hood, and “it helps to concentrate the sound; the vibrations.” Beethoven used an ear trumpet, which was the main method of hearing aid device used in the 1880s. He makes no use of sign language or lipreading. When Beethoven drinks in a bar, his friend has to shout into the ear trumpet. When he meets up with Anna, he uses the ear trumpet to understand what she’s saying. She has to repeat herself a couple of times. When we see Beethoven conducting his orchestra, he’s wearing an Alice band that holds the ear trumpet in his ear, and he’s conducting with both hands. These scenes clearly show that Beethoven is trying out different methods of hearing devices, which was accurate for those times. This attention to detail shows just how important it is for filmmakers to use research as a powerful tool in representing the right d/Deaf characters. Because of the accurate portrayal of the devices Beethoven used in that period, the audience has an emphatic portrayal of Beethoven’s struggles and courage.

In Dig, the language that is spoken throughout this film is ASL (American Sign Language) between Jane and her father. This is an accurate representation of the type of sign language that is used in the United States. Jane also refuses to use her voice and doesn’t use her mouth to form the words, which might not be as believable as the sign language. Previously, she was able to speak like a hearing person, so why can’t she form the words anymore? The muscle memory of her speaking with her voice should be ingrained inside of her. It feels inconsistent that she can’t form the words with her mouth. Early in the film, it is revealed that she now only has 10% hearing in her left ear, and 3% in her right ear. Her father wants her to get cochlear implants, and it is clear that he thinks it will be a ‘magic cure’ to Jane’s problems. Also, her father has been writing on notepads to communicate with her. ‘You’re pretty good with that lipreading stuff,’ her dad says after she spies on him making a shady business deal. How is it possible that Jane mastered the difficult skill of lipreading within just one year? This is not realistic nor believable, for lipreading is an incredibly tricky thing to learn, and it takes years of practice just to get a few words and sentences right. Most of the time, it’s guesswork at best. The lack of complexity in Jane’s d/Deaf and hearing journey could have been enriched through deeper research.

9. Sound

In Copying Beethoven, there is a scene where the audience claps hands and cheers after Beethoven finishes his final symphony performance. The sound is purposefully cut off, and we don’t hear the audience. Then Anna beckons for Beethoven to turn around so he can see the audience, and immediately the sound goes up again. We get a glimpse into the world of a profoundly d/Deaf person who can’t hear anything. Sound can be a powerful aid in inviting the audiences to experience a d/Deaf person’s world from their point of view. It also enhances the emotional impact on its audiences, and it serves as a fantastic reminder of how the loss of sound can profoundly alter one’s perception of reality.

In Dig, when Jane has the traumatic experience of seeing her mother shot in front of her, the sound abruptly cuts out the moment she ‘loses’ her hearing. It is terrifying as an audience to experience the sudden loss of sound, and we get to experience it with Jane. Sound is a complex and complicated experience for every individual. Films are unique in the sense that they can show us different perspectives and give us a glimpse into worlds we would never otherwise get to experience.

However, in the other two films –See No Evil, Hear No Evil & Mr. Holland’s Opus –the sound is not experimented with. We as the audience don’t get to experience the world from the d/Deaf person’s point of view. This film was clearly made for hearing audiences and hearing audiences only. Unfortunately, the d/Deaf character’s point of view is excluded from both films. These films missed the opportunity to create a more inclusive narrative that could resonate with both hearing and d/Deaf viewers.

When making films with d/Deaf characters, filmmakers are given the unique opportunity to think bigger than just the hearing audiences. Through intentional changes and adaptation – sound design, framing, sensory cues, close-ups – filmmakers can move beyond simple storytelling and include the d/Deaf audiences in the narrative.

10. Accessibility

When it comes to films, subtitles are probably the easiest way to make them fully accessible to d/Deaf persons. There are various types of subtitles available worldwide: captions, translated subtitles, Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing (SDH) or descriptive subtitles, and HoH (hard-of-hearing). (Charlie Little, 2023) “In the early days of cinema, silent films were ‘democratic’ insofar as they could be enjoyed by the hearing and the hearing impaired alike… With the advent of talking pictures, the hearing impaired were largely marginalized; cut off from a source of entertainment they once enjoyed,” writes Amyus in his article titled “Subtitling for Cinema: A Brief History.” (Amyus, 2018)

It seems like all four films were made with the hearing audience in mind. When it was shown in cinemas, there were no subtitle options available. The first film – See No Evil, Hear No Evil– came out in 1989; Mr. Holland’s Opus was released in 1995; Copying Beethoven in 2006; and Dig premiered in 2022. Subtitles have come a long way, however. “From the early days of intertitles in silent films to the sophisticated technology of today’s subtitles, the subtitling industry has evolved dramatically… the future of subtitles looks promising.” (Amberscript, 2023)

“There must be collective and collaborative efforts and proactive actions towards the standardized, uniform provision of high-quality, accessible screenings…” writes Charlie Little in his article “Standardising Accessible Cinema: Less Talk, More Action” (Charlie Little, 2023) Little also writes that “…the industry’s commitment towards Deaf access should be daily and event-to-event, screening-to-screening. There shouldn’t be a swell or momentum but rather an ongoing, continuous effort towards embedded, defaulted accessible and inclusive practices.” (Little, 2023)

It is my recommendation that filmmakers look towards adopting the “Off-Screen Cinema Subtitle System” for all their future film projects. In 2013 and 2014, Jack Ezra developed this system specifically for the d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing persons. How is this done? Invisible subtitles appear on the screen, and anyone who wears a lightweight pair of glasses can see the subtitles displayed on the screen. In this way, both the hearing and d/Deaf person are satisfied. “Our system places a special ‘inconspicuous’ display along the bottom of the movie screen, which looks blank. This way it does not distract the general audience…” (Amyus, 2018)

SURVEY RESULTS

Using the trends, I compiled a survey with a list of questions, and I approached fifteen d/Deaf individuals and recorded their responses. After receiving all 15 participants’ feedback, I counted all the positive answers, and then the negative answers together. From those results, I made pie charts with the positive and negative percentages.

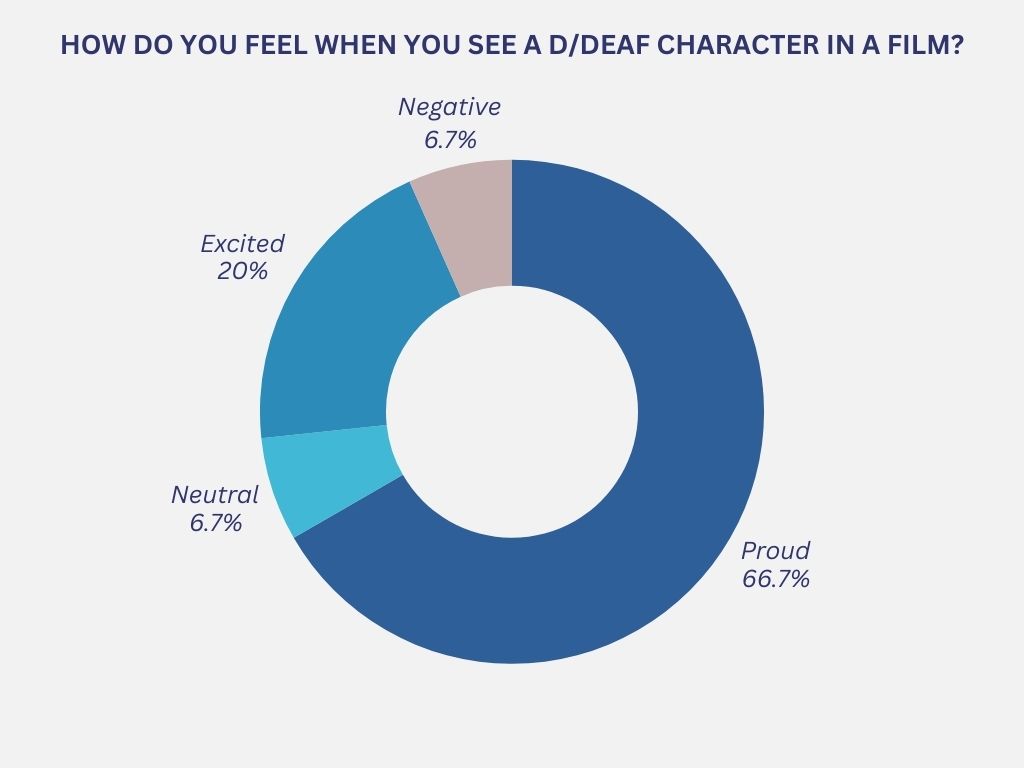

Q1: How do you feel when you see a d/Deaf character in a film?

According to this data, the inclusion of d/Deaf characters in film has a generally pleasing and elated impact on the d/Deaf audiences. Feelings of pride and excitement show the value of representation in media as a tool for inclusivity and awareness. The single negative response and one neutral response show areas of doubt, such as whether there are films where representation feels stereotyped or disrespected. Overall, the data reveals the significance of authentic narrative in d/Deaf onscreen characters.

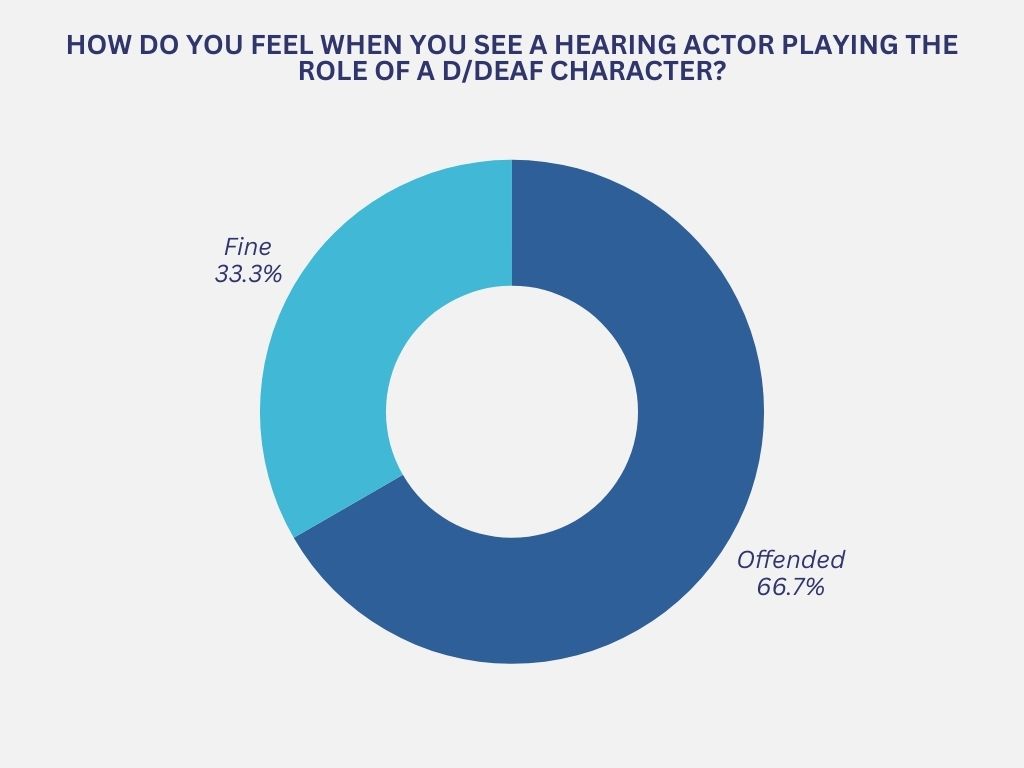

Q2: How do you feel when you see a hearing actor playing the role of a d/Deaf character?

The data indicates a strong preference for accuracy and authenticity when it comes to portraying d/Deaf characters. A majority of the group’s responses show that they feel ‘Offended’ when hearing actors are cast to play d/Deaf roles. They feel that talented and undiscovered d/Deaf actors are overlooked, marginalizing them as a group. The minority’s response was ‘Fine’ with hearing actors being cast in the roles of d/Deaf characters, which shows that there are a few who believe that hearing actors can play believable d/Deaf onscreen characters. Overall, this data strongly highlights the importance of casting d/Deaf actors in d/Deaf onscreen roles.

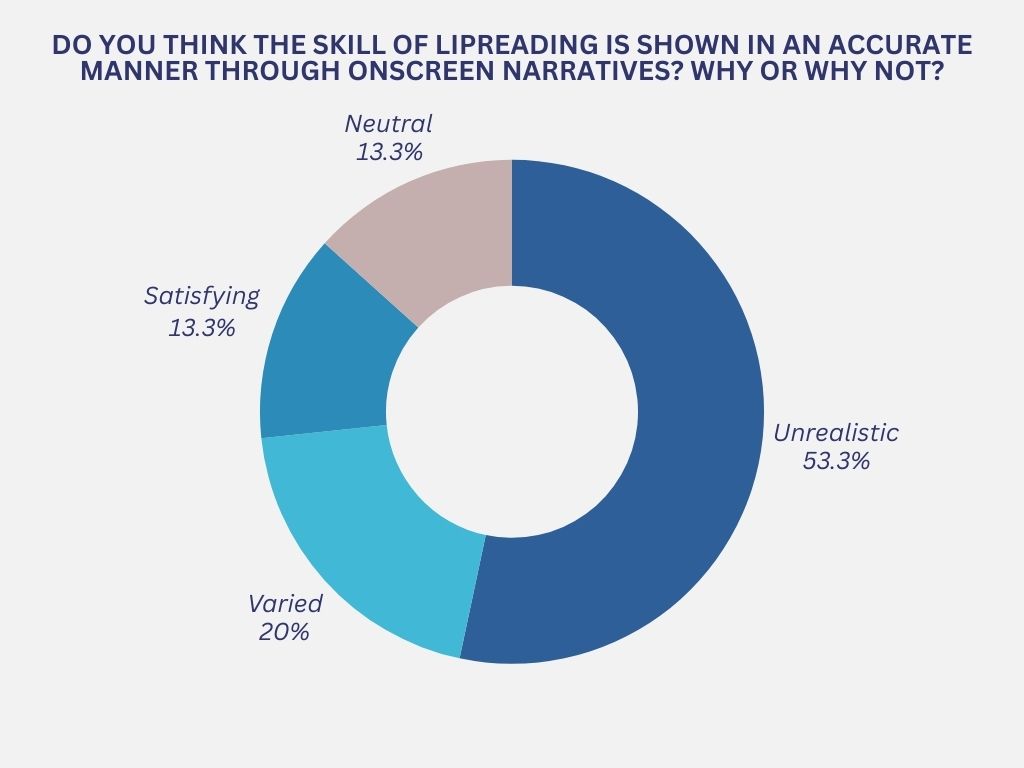

Q3: Do you think the skill of lipreading is shown accurately manner through onscreen narratives?

This evidence suggests that many d/Deaf individuals feel that the skill of lipreading in onscreen film narratives lacks accuracy and consistency, with “Unrealistic” being the dominant response. This reflects frustrations with the way films oversimplify or misrepresent the skill. The respondents feel that the narrative often doesn’t show the challenges, inaccuracy, and limitations of lipreading. While the mixed opinions – satisfying and/or varied – show that certain other films did portray it more accurately. Overall, this data suggests how important it is for filmmakers to showcase lipreading accurately by consulting and collaborating with d/Deaf persons. In this way, real-life experiences and knowledge will enhance the narrative.

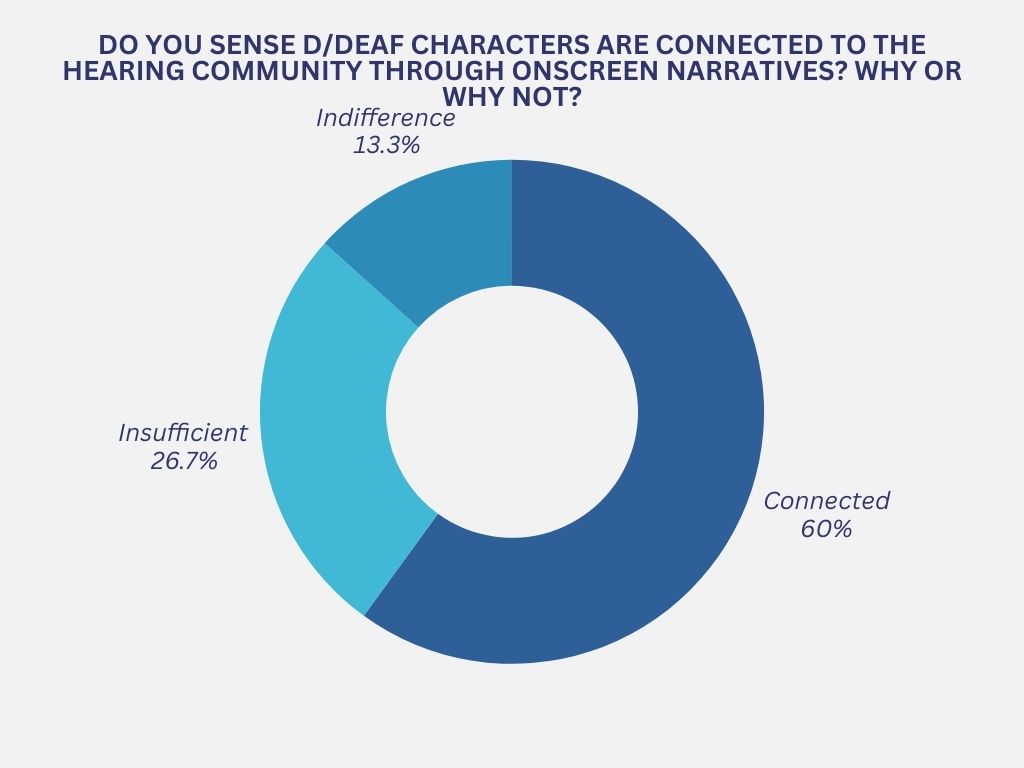

Q4: Do you sense d/Deaf characters are connected to the hearing community through onscreen narratives?

The statistics indicate that while many d/Deaf persons feel that the onscreen narratives show a meaningful connection between d/Deaf and hearing characters in the society and community, there still remains room for improvement. The majority feels “Connected”, which shows integration and interaction. It also fosters understanding and inclusivity. However, the “Insufficient” and “Indifference” respondents feel concerned that these connections are superficial and/or one-sided.

This difference of opinions could come from the lack of showcasing d/Deaf characters with the depth it needs. The d/Deaf character is complex, and it comes with its own challenges, cultural differences, and communication issues. Filmmakers need to realize that they need to do proper research so that the gap between the d/Deaf and hearing communities can be bridged.

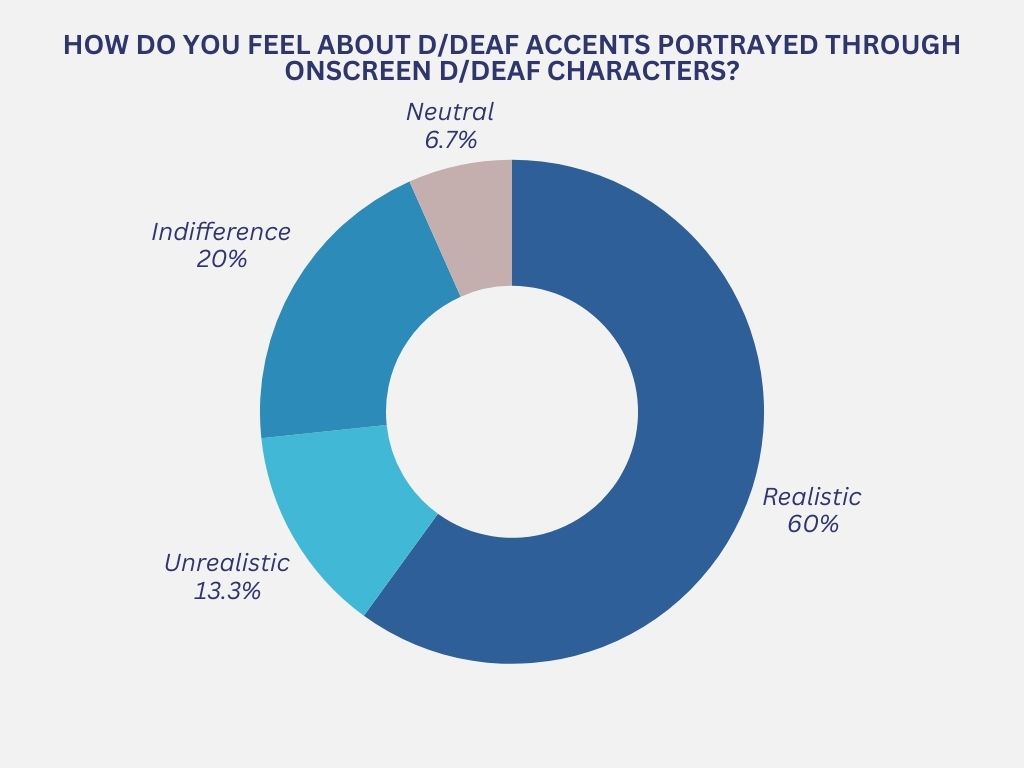

Q5: How do you feel about d/Deaf accents portrayed through onscreen d/Deaf characters?

This data indicates that most d/Deaf respondents see the portrayal of the onscreen d/Deaf accents as realistic. This feedback is positive and shows authenticity in representation. The “Unrealistic” and “Indifference” responses show that not all portrayals are accurate or correct representations of the d/Deaf person. This might come from the fact that some d/Deaf accents have been exaggerated and/or treated insensitively. This data highlights how important it is to create thoughtful and respectful characters. Treading on d/Deaf accents should be handled with sensitivity.

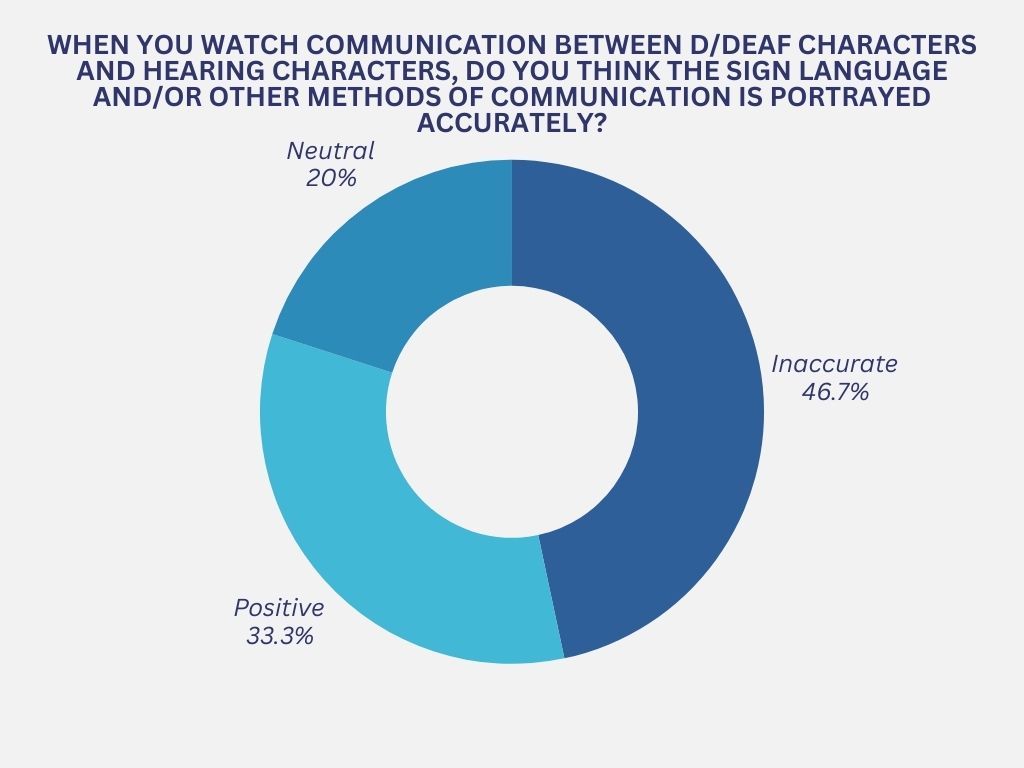

Q6: When you watch the communication between d/Deaf characters and hearing characters, do you think the sign language and/or other methods of communication are portrayed accurately?

The varied responses suggest that the accuracy of communication, such as sign language, between d/Deaf and hearing characters in film has been inconsistent. While some respondents see these depictions positively, others find them inaccurate. This shows a lack of authentic representations.

The “Inaccurate” responses reflect concerns about the incorrect use of sign language and the unrealistic ease of communication. However, the “Positive” responses indicate appreciation for narratives that make a genuine effort to represent these interactions accurately and respectfully.

This division of results shows that filmmakers need to work closely with d/Deaf consultants and communities to accurately show authentic depictions of communication methods. Accurate portrayals not only enhance the credibility of the narrative but also contribute to greater awareness and understanding of d/Deaf culture and the realities of their interactions with the hearing community.

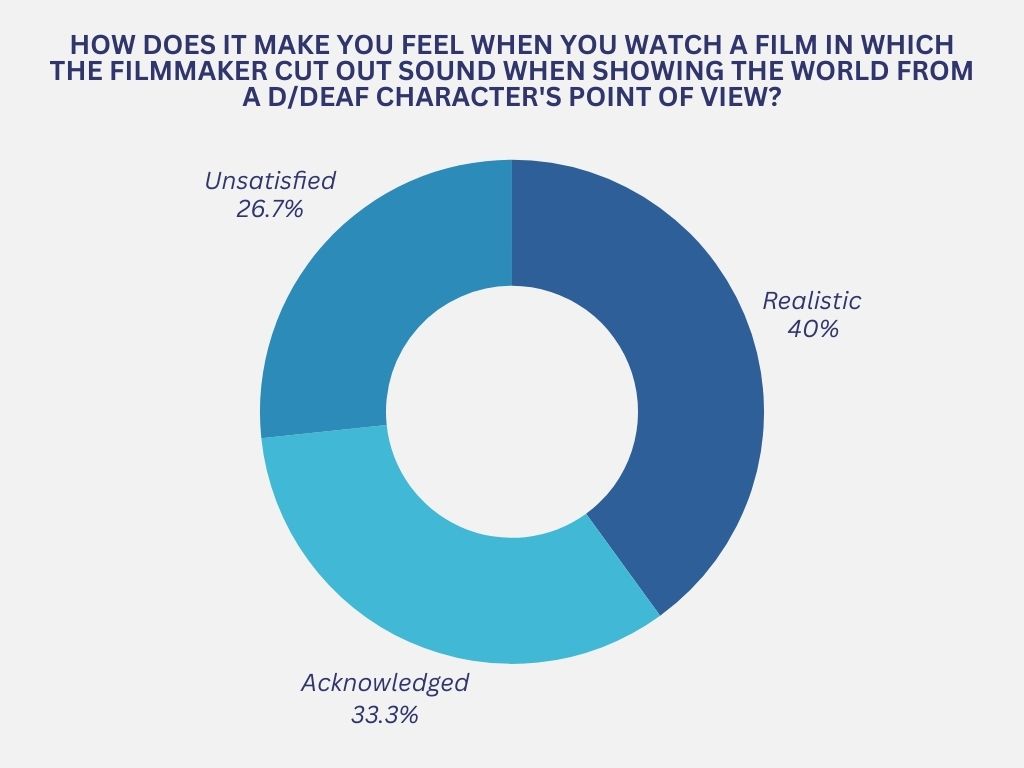

Q7: How does it make you feel when you watch a film in which the filmmaker cuts out sound when showing the world from a d/Deaf character’s point of view?

The reaction in this data is mixed. Even though it shows that cutting out sound to show the world of the d/Deaf character can be impressive, for others, it tends to fall short. The d/Deaf respondents who feel that it is “Realistic” or “Acknowledged”, appreciate and grasp what the filmmaker is trying to convey. They believe this kind of filmmaking breeds empathy and understanding.

However, the “Unsatisfied” responses show that this kind of technique doesn’t show the full complexity of what it means to be d/Deaf, as deafness itself is a wide spectrum of frequencies and sounds. It may make the d/Deaf onscreen character look incomplete and/or one-sided.

While cutting out, fading, and/or reducing the sound might be an effective way of drawing the viewer into the d/Deaf person’s world, thoughtful consideration is important. Collaborating with d/Deaf artists and/or consultants can help filmmakers create the right balance between artistic interpretation and respectful representation.

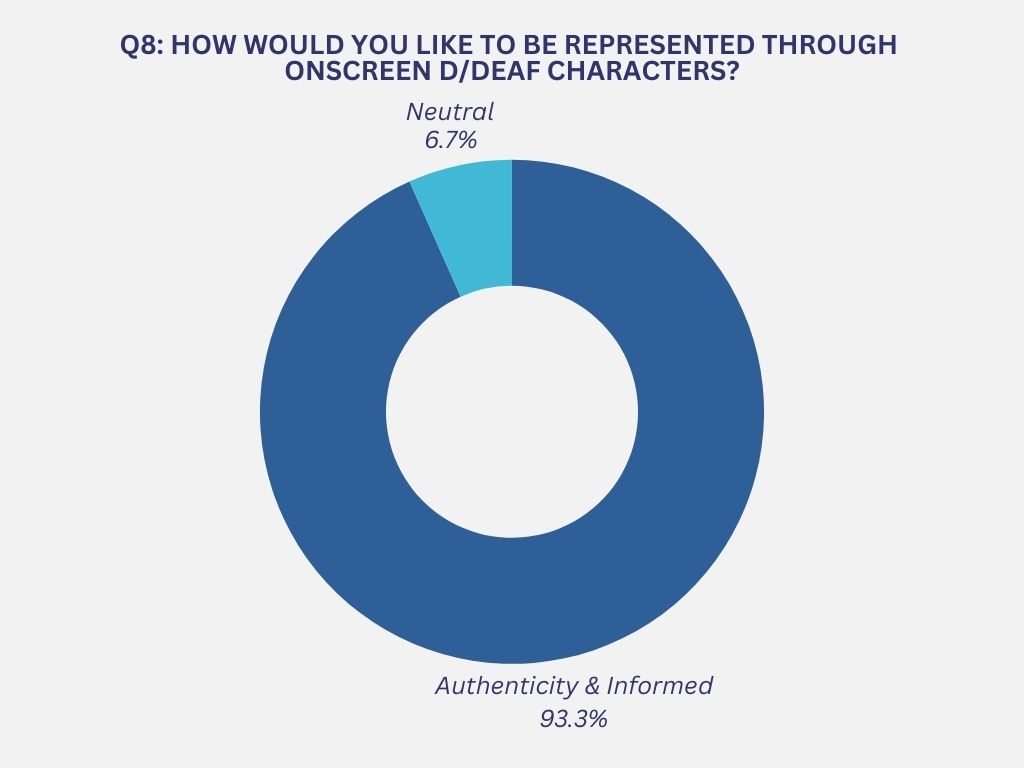

Q8: How would you like to be represented through onscreen d/Deaf characters?

An overwhelming majority of the respondents believe that authenticity is important when it comes to creating onscreen d/Deaf characters. There is a strong desire and need for narratives and characters that inform and accurately reflect the lived experiences, culture, and complexities of the d/Deaf person, as well as the Deaf community. The one neutral response shows indifference, which only strengthens the belief that the majority of d/Deaf individuals want respectful, truthful portrayals of d/Deaf onscreen characters. This collective data reflects that there should be a significant movement towards more thoughtful, respectful representation in film.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCREENWRITERS & FILMMAKERS

Filmmakers and screenwriters can create richer, deeper, and more respectful onscreen d/Deaf characters. In this way, inclusivity and authenticity will be fostered to represent the d/Deaf community in an accurate, respectful way.

Authentic Representation: It is the filmmaker’s responsibility to ensure that screenwriters do the necessary in-depth research to create narratives and storylines that accurately represent d/Deaf onscreen characters. Keep in mind their cultural representation, such as whether they are part of the hearing community or the Deaf community. By adopting these strategies, authenticity and positive representation can come through in the film.

Casting d/Deaf Actors: Avoid and refrain from hiring and casting hearing actors to play the roles of d/Deaf onscreen characters. The overwhelming responses in the data show a strong preference for actors who are genuinely d/Deaf. This will bring authenticity and respect to the d/Deaf individual as a whole.

Accurate Lipreading: Lipreading needs to be shown as a survival skill, not a superpower skill. Show the complexity and limitations where lipreading is concerned. Consult with d/Deaf persons and/or consultants to ensure that lipreading is shown accurately.

Depth in d/Deaf-Hearing Relationships: Create meaningful, emotional arcs and connections between d/Deaf and hearing characters. Steer clear from shallow, superficial, or one-sided portrayals. Instead, explore and research the communication challenges that might arise, cultural differences, etc.

Realistic Portrayal of d/Deaf Accents: Depict d/Deaf accents in a respectful and honorable way. Avoid exaggeration or insensitivity, and engage d/Deaf actors and consultants to ensure authenticity.

Accurate Communication Methods: Communication methods such as sign language need to be portrayed accurately according to country, province, and area. This includes showing the complexity of communications between d/Deaf and hearing individuals.

Sound and Sensory Representation: When showing the world from a d/Deaf character’s perspective, be mindful of using techniques like cutting out sound. While this technique can be impressive and remarkable, it should not oversimplify the d/Deaf experience. This technique should be handled with consideration, keeping in mind the complexities and wide spectrum of d/Deafness.

Engage with the d/Deaf Community: Work closely with d/Deaf consultants, actors, and community members to ensure all aspects of the portrayal are accurate, nuanced, and respectful. This can help to ensure the stories resonate with the d/Deaf audience.

Empowerment through Media: Films are a powerful tool when it comes to knowledge, education, and empowerment. Make sure that the d/Deaf characters are multidimensional, strong, complex, and well-rounded through thorough and accurate research.